(click here to read previous story: Nahant, MA)

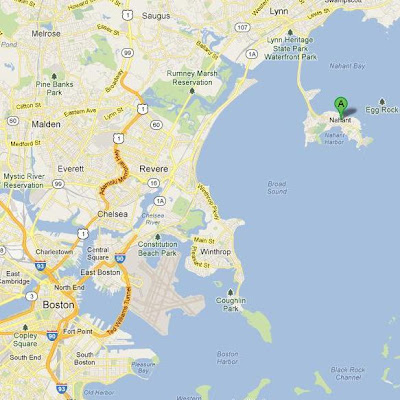

Between the ages of 5 and 11 (1936-1942) my grandfather, Dinon, lived on one square mile of land, a peninsula called Nahant off the shore of Massachusetts, just a little northeast of Boston.

Dinon's father, my great-grandfather Ralph, worked on the mainland end of the Nahant causeway in the town of Lynn, MA. He was a chemical engineer, working in the plastics division for General Electric. In 1936, he had a 5-year-old son, Dinon, and a pregnant wife, Babe. It was just 6 years after the start of the Great Depression, and he was fortunate just to have a job.

In September of 1939, Germany invaded Poland. By then, his sons, Dinon and Daryll, were just 8 and 3 years old. And, in spite of everything, he had been talking with Babe about even having a third child in another couple of years.

Something that is remarkably consistent in the way my grandfather, Dinon, tells his childhood stories is his tone of contentment and happiness. In spite of being born in the outgoing tide of the Great Depression and being a young boy as the second world war brewed and broke, Dinon's childhood memories are happy. I think it says a lot about my great-grandparents, Ralph and Babe, that Dinon's memories of the effects of the war on Nahant are all colored in the safety of adventure.

The first tangible effect was the sudden population of the golf course.

“When the war started, things changed, and we got more interested in what was going on with the war," Dinon said. "We lived half-a-block from the golf course [what is now called the Kelley Greens at Nahant], a real nice golf course. Then, all of a sudden, before the war started, before Pearl Harbor, the golf course became populated with barracks and soldiers."

|

| The golf course is the biggest white space, positioned to the west and north of Ft. Ruckman (source) |

Geographically, little Nahant played an important role as a gatekeeper for the Boston Harbor, located just to the south. Combined with its height (above sea level), Nahant was tactically desirable, and became the most heavily armed site for the defense of the harbor1.

|

| Today: Battery Gardner Gun 1 and the Ft. Ruckman fire tower (source) |

This is what my grandfather remembers about dozens of military personnel suddenly appearing where he lived - mascot status and peeled sunburns.

I have to wonder what my great-grandparents were thinking as they watched troops, equipment, and antiaircraft weaponry arrive on their tiny coastal home. This was still pre-Pearl Harbor, but the radio was filled with news about an aggressive Germany and bombings in Europe and President Roosevelt's "fireside chats". What went through their minds about their two young boys when ration stamps were issued, black-out curtains and curfews were enforced, and the men and women of their community were called to help with the war effort?

“My dad was air raid warden, and his job was to go around and make sure everybody’s black-out curtains were closed so you couldn't see any light," my grandfather said. "We didn't want the German submarines to know where the coast was, and of course, this is a time before radar and sonar, so the U-Boats would probably have to surface and see where land was. So my dad had a regular route of certain streets, and he'd go his rounds and check to make sure the black-out curtains were in fact all closed."

Even the automobiles had black-out standards for protection, and slotted covers were attached to headlights.

“The vehicles had what looked like cats' eyes for illumination," Dinon said. "The light from the headlights were directed down instead of out in front, and they were a lot dimmer than the typical headlight. But there were going very slow, and they didn't have the traffic at night at that time, in 1941 and ’42. It was an entirely different time.”

But even if a U-Boat had floated up and a few Germans had come ashore, there's probably not much Ralph could've done.

"His only weapon was a billy club, a small fat billy club with a lead core in it. It was heavy, but I don’t know what they expected him to be able to do with it … y'know, if the Germans landed and had guns, what’re you gonna do with a billy club against a luger?”

But in spite of the potential threats and uncomfortable restrictions, life - work, school, laundry and meals - had to go on.

|

| Dinon, on the porch of the Nahant house |

“We had rationing of food," my grandfather said. "You had to have blue stamps for canned goods, and red stamps for meat and dairy products. When you went shopping, you had to have your food stamps. And then there was a ration card for gasoline, and if you were declared as needing gasoline to get to and from work, you were given a gasoline ration for that. I know my father had [gasoline] rationing.”

Later in life, my grandfather developed a stamp-collecting hobby; in his collection, he still has some of the ration stamps.

Not terrifying, uncomfortable, or uneasy.

Interesting.

The Boyer family continued to live in Nahant until 1942, when Ralph took a job at a paper mill 1,200 miles away in Wausau, Wisconsin. Dinon was 10, almost 11, and his brother Daryll was about 5 years old; their baby sister, Glenda, was either on the way or newly arrived at that time. Dinon remembers being angry about the move, because he loved Nahant and being able to see the ocean in two directions from his bedroom window. He never lived on the coast again. But, years later, he revisited the little peninsula with my grandmother, Elizabeth.

“Liz and I went to Nahant when we drove out East, and we decided we’d go visit where I lived," he said. "And so, we drove up to the house, and we parked across the street from it and I started to take pictures of the house. Well, that really upset the owner – the woman’s husband wasn't there – and so this woman called her son, and her son said, 'Go out and find out why they’re taking them.' And so, when I told her that I used to live there when I was a kid, she invited us in and they had not changed that house really at all, it was still the same as I remembered it as a kid. She allowed us to go upstairs into the bedrooms, and ... I could still see the ocean in two directions.”

1 Source: http://www.coastdefense.com/nahant.htm